Dr. Tiaan Eilerd stops for a moment when he thinks of Alison Botha’s attackers, who were released on parole earlier this week. He admits that he shouldn’t say what his initial reaction to the news was, but he is sure of one thing: it is unacceptable.

“It is putting people who commit extremely heinous acts back into society and expecting them to function in it. There is no way,” Eilerd told RNews on Thursday.

Frans du Toit and Theuns Kruger brutally raped, mutilated and left Botha, then 27, for dead in the midnight hours of 18 December 1994. They were released on parole on Tuesday 4 July this year, after almost three decades in prison. They were initially given a life sentence.

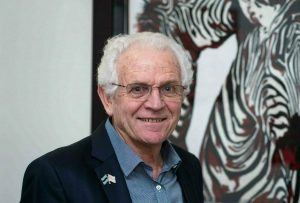

It was Eilerd who found the bloodied, injured and half-naked Botha along the quiet road in Gqeberha. For almost an hour, he sat and watched over her while they waited for an ambulance. He even drove with her all the way to the hospital – he didn’t want to leave her.

There he saved her life, and yet, when he thinks of that night, he knows that in many ways Botha also saved his life.

Eilerd’s dismay at the parole news is accompanied by a mistrust in the justice system, which he fears is not built to fully rehabilitate criminals.

“The big thing I realized is that there are an awful lot of bad people out there. Based on what people see in the hospitals of how people, especially women, have been assaulted, children assaulted, murder… one realizes that society is sinking.

“More than half of the stuff is not even reported. We have some of the highest death rates in the world, and the rape rate is just as high. It gives you an indication of what is going on in our legal system, which is supposed to protect us.”

A life-changing evening and lifelong friendship

It has now been almost three decades since Eilerd’s paths crossed with Botha’s.

There were knife wounds all over her body, her abdomen was cut open and her throat almost completely cut when Eilerd, then 20, came upon Botha. However, her bloodshot eyes stared intently at Eilerd, despite her broken body, she was still conscious.

It was her eyes that still stick in his mind today when he thinks about the incident.

“She couldn’t speak. She lost a lot of blood and was mushy,” he recalled that night.

“Looking into her eyes was the only way to see if she was still awake.”

Botha was hijacked and kidnapped by Du Toit and Kruger in front of her apartment block in Gqeberha on 18 December 1994. They drove with her in her own car through the streets of Gqeberha before they finally drove out to the Noordhoek road where they pulled off the road.

She was brutally raped and mutilated by Du Toit and Kruger that night in the darkness between bushes. She suffered around 30 stab wounds, with serious injuries to her neck and abdomen.

There they left her for dead.

She wrote the names of her attackers, Frans and Theuns, next to her in the sand before tying her denim blouse around her stomach. Her intestines were no longer in her body due to her injuries, she needed her blouse to hold them as she crawled towards the road.

With her other hand she had to hold her head steady, because of her throat wound she could not control her neck.

A car drove past Botha’s bloody body, but did not stop. It was Eilerd who finally stopped by her place, spoke to her and forged a lifelong connection with her that night.

At that stage Eilerd returned with a group of friends from a nearby night club to the caravan park where they were on holiday. Little did he know that his life would change irrevocably that night.

“Wow, not good,” he remembered how she looked that night, “Really, really bad.”

The ambulance was called and Eilerd sat next to Alison and waited, her hand firmly in his. They communicated by means of handshakes, “one shake for yes, and two for no.”

After almost an hour, the ambulance finally arrived at the scene, but Eilerd did not want to let go of her hand. He got into the ambulance with her.

“I think at one stage I didn’t want to let her go. You don’t know what will happen next. You could see that this is something that should not happen to anyone.”

Eilerd’s life took a different course after the incident – he realized that he had to pursue his dream of becoming a doctor.

He was studying veterinary technology at the time, and considered dropping out. His choice to make a complete turnaround in his future plans brought Eilerd a long but satisfying road.

“I started at the bottom,” he recalls.

He initially did a paramedic course and worked as a paramedic for a while before returning to the army. There he was trained as a nurse. After his time in the military, he jumped into clinical technology where he specialized in critical care.

He finally obtained his medical degree at the Sefako Makgatho University of Health Sciences in the early 2000s.

During his internship, he had the opportunity to assist during Botha’s second emperor.

“For someone who was not expected to be able to have children one day, a second caesarean section was incredible. It was very special.

“Our friendship is still as strong as that first night,” he says.

When Eilerd thinks about the past three decades today, he knows that without Botha, his life would not have looked like it does today.

“When I decided to study medicine, it was a very long way to get there, but if it wasn’t for the incident, I probably would never have done it. Ten to one I would not be sitting where I am today, knowing the people I know today. Things could have turned out completely different for me.”

“I met my wife in the army, I have three children that I would never have had ten to one. It turned my life upside down.”

Additional resources: Alison, I have life