Although they cannot speak, the dead have a lot to say.

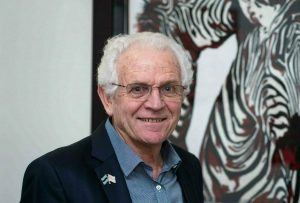

Thus writes prof. Ryan Blumenthal, a forensic pathologist attached to the University of Pretoria, in his book Autopsy: Life in the Trenches with a Forensic Pathologist in South Africa.

However, due to the glaring shortage of board-certified forensic pathologists nationwide, there are not nearly enough experts to “listen” to the multitude of bodies lying in South Africa’s overcrowded morgues. Many of them were the victims of violent crime.

Where the USA needs five pathologists for every million people, South Africa “with its endemic unnatural death burden” needs six forensic pathologists for every million people, says Blumenthal in an interview with RNews.

This means that South Africa, with a population of more than 61 million people, should have at least 330 of these experts. Last year, however, only around 50 forensic pathologists worked in the public sector. This figure refers specifically to forensic pathologists who are certified by the Health Professions Council of South Africa (HPCSA) and registered with this council.

Most of them work in Gauteng and the Western Cape. The Outlier reports that KwaZulu-Natal, one of the provinces with the most people, had only two qualified forensic pathologists in 2023.

This is far too few for the average of 70,000 unnatural deaths that are reported annually in the country.

Unnatural deaths include murders, of which around 70 are committed daily in South Africa. Road accidents and suicide also make a large contribution to these figures. In the case of unnatural deaths, full medico-legal investigations are carried out, which according to Blumenthal is subject to strict legislation in South Africa.

Expertise wanes

In addition to regulatory legislation, forensic pathology must also comply with the national code of guidelines for this practice, as well as the rules and regulations of the Health Professions Council.

Next of kin may not refuse legal medical examinations, and the government has power of attorney in this regard, according to Blumenthal.

“Forensic pathologists assist in carrying out forensic examinations, which include investigating the circumstances surrounding the person’s death. The autopsy (autopsy or postmortem examination) is only a small part of the overall death investigation.

“So forensic pathologists are specialist death investigators who help bring closure.”

In South Africa, however, many next of kin will have to wait years to find answers and reassurance – if ever.

“I believe the shortage of forensic pathologists will have a negative effect on South Africa’s ability to provide a quality death investigation service.

“We need at least 150 forensic pathologists (minimum) just to be able to play the game,” says Blumenthal.

Even then, the work is likely to be too much, as homicide in South Africa has increased by 36% since 2017. There is also not exactly an increase in the number of people pursuing a career in forensic pathology in the country, while existing experts will probably leave the profession within the next ten years.

“The number of forensic pathologists currently completing training programs does not nearly compensate for the number of pathologists who will retire, emigrate or leave the workforce within the next decade and a half,” he says.

Meanwhile, the population is growing by leaps and bounds, while morgues in the country are getting fuller.

Gauteng, which has a population of more than 15 million, currently has only 16 pathologists working in the public sector, reports The Outlier. This figure reflects the official statistics of the provincial department of health.

Last year, almost 22,000 bodies, approximately 60 per day, were sent for autopsies in this province.

If all the required autopsies had been done last year, each of these experts would have had to examine a total of 1,367 bodies. It takes about three hours (or longer with complicated cases) to complete one examination and every forensic pathologist in Gauteng would therefore have to work 12-hour shifts seven days a week just to get the minimum done.

Gauteng has 11 forensic morgues, but most bodies, about 40%, are sent to Germiston and Johannesburg.

In the US, guidelines state that forensic pathologists may not perform more than 250 autopsies per year. If this happens, the institution may lose its accreditation.

In an article by Sue Segar published on the University of Pretoria’s website, Blumenthal says that forensic pathologists in South Africa each perform between 450 and 650 autopsies per year.

However, Blumenthal emphasizes that there are other medical experts, including general practitioners and clinical assistants, who perform autopsies in South Africa – otherwise the work would certainly never be done. However, these medical experts are not board-certified forensic pathologists specifically trained in this field.

Problem getting worse

In addition to a shortage of forensic pathologists and other forensic experts in the country, there are also other problems that make the matter worse. This includes unidentified bodies and a shortage of equipment.

By February this year, there were 776 unidentified bodies in Gauteng morgues.

According to the statistics which the department provided to the DA in response to parliamentary questions in April this year and which RNews had under their eyes, things are just as dire in other provinces.

In KwaZulu-Natal there were 1,336 unidentified bodies followed by Limpopo with 283 unidentified bodies, North West with 266, Mpumalanga with 82, the Free State with 73 and the Northern Cape with 51 unidentified bodies.

Dr. Joe Phaahla, Minister of Health, says it is policy that a body that is not claimed or identified within seven days is transferred to a cooler. Should this body still not be identified after another 30 days, the municipal council that has jurisdiction over the relevant facility must ensure that a pauper’s funeral takes place.

It is a sad, lonely end for these nameless victims.

News24 reported that a total of 400 pauper funerals were carried out in the Western Cape alone last year.

Phaahla emphasizes that records of these people are maintained and stored as completely as possible, including photographs, fingerprints as well as blood and tissue samples.

Defective infrastructure

Many of the public facilities in the country that do perform autopsies are further hampered by problems such as broken refrigerators and inadequate infrastructure. Some are used only as storage facilities and therefore do not perform autopsies.

In Mpumalanga, two of the 21 forensic pathology facilities, on Barberton and Belfast, are used as storage facilities, while the facility on Standerton has infrastructure problems and is therefore unable to perform autopsies.

In the Northern Cape, one of the province’s six facilities cannot perform autopsies because a pathologist has not been appointed. There are also problems with infrastructure at the facility on Calvinia.

According to the department, three out of the 15 forensic pathology facilities in Limpopo have “no operational resources” to perform autopsies. The relevant facilities are on Musina, Lephalale and Thabazimbi.

The Western Cape uses two of its 18 facilities as storage facilities, at Laingsburg and Riversdale, and one at Swellendam as a training facility.

In April this year, a total of 72 refrigerators at 74 morgues nationwide were out of order. However, it is not known how many refrigerators each mortuary has.

According to the department, refrigerators are serviced every three months and there are contingency plans to deal with these kinds of problems.

Dead end street

However, the shortage of forensic pathologists remains one of the biggest problems, which has a far-reaching effect on justice.

This leads, among other things, to the postponement of court cases and consequently also setbacks with legal proceedings.

Because of the enormous workload, investigations often have to be rushed, which puts the credibility of such an investigation in jeopardy, Blumenthal said in an interview with The Outlier.

This obviously has an influence on the outcomes of hearings.

“Solving murders will become increasingly difficult without enough forensic experts to analyze evidence.”

In his book, Blumenthal offers a possible explanation for the government’s apparent failure to prioritize forensic pathology in South Africa: “Forensic pathology is always going to come last because our patients are already dead.”

Additional resources: Autopsy: Life in the Trenches with a Forensic Pathologist in South Africa by prof. Ryan Blumenthal and the article “Despite rising crime rate, SA has dire shortage of forensic experts” by Gemma Gatticchi published by The Outlier has been published.