Declador Rimeldeoudje walks through the fields with thousands of stalks that he hopes will yield a brilliant cotton harvest – but he also knows very well that the future of Chad’s so-called white gold is as unpredictable as the rain.

For decades, cotton was the lifeblood of southern Chad. But the prized crop’s future hangs in the balance.

At the entrance to the village of Kagtaou, about 60 km outside Moundou, the capital of the south, stands a giant container filled to the brim with cotton.

CotonTchad, a semi-private company that is supposed to buy the cotton, has still not fulfilled this promise and producers fear the unpredictable rain will ruin the crop even before it has been sold.

“We like cotton, but it’s just getting too difficult. The climate is unstable and this is a real concern. It affects the tonnage,” explains Rimmeldeoudje as he squints against the scorching sun.

The 24-year-old farmer’s profits tumbled to a third of what they were in the previous year.

Almost everyone in Kagtaou earns an income from cotton.

But more and more of them are on the brink of despair due to the damage caused by climate change – and the ongoing conflict between farmers and nomadic herders.

“Evidence of climate change – infrequent rainfall that sometimes causes droughts and sometimes sporadic floods – leads to large drops in production,” says Laohote Baohoutou, a climatologist attached to N’Djamena University.

Climate change

Nomadic livestock farmers from the dry Sahel region in the north chase their animals through the fields belonging to farmers in the south, or they let the animals graze there. There are also disputes over who owns certain pieces of land.

In March, at least 23 people were killed in fighting that lasted for a week. Women and children are often the victims of this frequent conflict.

Intense rain is a new threat. The United Nations (UN) says floods in 2022 destroyed more than 350,000 ha of crops and led to 20,000 livestock deaths in the country.

The south was the hardest hit.

“It’s really discouraging,” sighed Rimeldeoudje.

“It feels like the south doesn’t even appear on a map of Chad anymore. We get no financial support.”

Since April, Africa has experienced several extreme climate events.

The west reeled under heatwaves with temperatures of up to 48 °C.

The east was again peppered with torrential rains that caused deadly floods in Kenya and Tanzania.

Forgotten

It was once one of Chad’s most thriving agricultural sectors, but now the cotton industry has tumbled as a share of GDP. Exports fell from 2.15% in 2015 to 0.7% in 2020, according to figures from the World Bank.

The prospects for Chad’s white gold will also have an influence on voters in the south of the country when around 18 million eligible voters vote for a new president on Monday.

Mahamat Idriss Deby Itno, who took control of the country three years ago after a coup, is competing with the prime minister he appointed in January.

Some believe that Succes Masra, once an opponent and now an ally of Deby, is a sham candidate who is there to create the illusion of democracy during an election that Deby will narrowly win.

Others say that Masra (40), who attracts large crowds of supporters, is a real candidate and that he can force Deby into a second election round.

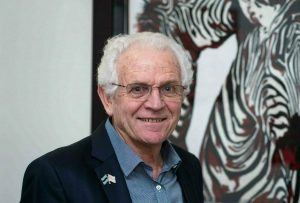

Jean Benaudji, head of the association of cotton producers in Kagtaou, intends to vote for Masra.

“He is the only one who can secure support for the cotton producers; producers who have been forgotten and left behind by the rest of the country,” he says.

Masra, from the south, makes promises of “justice and equity” that resonate with many unemployed cotton growers who get nothing when their crops are destroyed by other people’s cattle or rain.

“His slogan is justice, equality and peace. This is what I want and this is why he will get my vote,” says Rimmeldeoudje.