“Any reduction in load shedding is welcome, but we must not allow it to lull us into complacency. Our power grid still cannot keep up with our economy.”

This is what Busisiwe Mavuso, CEO of Business Leadership South Africa (BLSA) and former Eskom board member, says after the electricity minister explained the current state of affairs regarding the power crisis at the weekend.

Kgosientsho Ramokgopa on Sunday gave candid feedback on progress to reverse the ongoing power crisis. He says Eskom’s plants have made tangible progress in the past two weeks and the power supplier’s energy availability factor (EAF) currently stands at 60%.

Eskom was supposed to have already achieved an EAF of 60% in March, but now intends to reach a rate of 65% by the end of the year. Ramokgopa says the progress that has been made is one of the main reasons why less load shedding has been introduced recently.

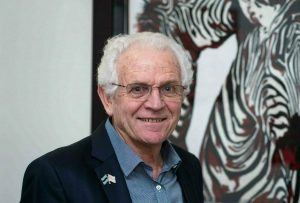

The independent energy expert Chris Yelland says that despite the slow progress that has been made, it seems at least that there are steps in the right direction.

“Although it is still unclear at this stage how sustainable this progress is, it is necessary to be grateful for the progress that has been made,” he says.

According to Yelland, the absence of load shedding throughout the day is attributed to the fact that there are fewer breakdowns.

“It is therefore clear that Eskom’s efforts to reduce the number of interruptions are definitely paying off,” he says.

The number of unplanned breakdowns at Eskom plants has reduced by 3,000 MW over the past few days. Only a month ago, the generation capacity that had to be given up to breakdowns was between 18,000 MW and 19,000 MW, while now it is between 14,500 MW and 16,000 MW.

“It is difficult to say whether any lasting progress has been made just by looking at the past few weeks, but Eskom must be given due credit for securing a slight improvement in the availability of power in June,” says Yelland. .

The national energy crisis committee (Necom) has also done a lot in the past year to reverse the country’s energy outlook. Among other things, Necom helped ensure that private generation development was stimulated by making amendments to the Electricity Regulation Act. As a result, around 4,200 MW of new power generation capacity has been registered with the National Energy Regulator (Nersa) over the past year.

Mavuso says this is a remarkable achievement which is essentially the key to ending the power crisis.

“Along with the progress that has been made to encourage households and businesses to invest in solar power, it is clear that there is a great response to tackle the power crisis,” she says.

“Although we do not have details on exactly when the hundreds of new plants will come online, the lead times for solar and wind facilities are much shorter than plants using fossil fuels.

“This is why experts predict that load shedding will begin to come to an end by the end of 2025.”

Ramokgopa says there is also progress with municipalities incentivizing customers to invest in embedded generation by paying them for feeding into the power grid.

Cape Town is at the forefront of this initiative, but several other areas, such as Nelson Mandela Bay, Buffalo City and Ekurhuleni, are trying to do the same.

According to Yelland, however, other cities, such as Johannesburg and Tshwane, miss the mark with this.

“Although these cities or municipalities have many plans and intentions to do this, they are just too limited financially.”

Municipalities can also work faster with less bureaucratic red tape to enable private generation, Mavuso believes.

More capacity needed, but who will pay?

In addition to all the progress that has been made, it will mean nothing if there is no more capacity available in the power grid.

“More network capacity is needed to expand the production of renewable energy,” says Mavuso.

“But to ensure this costs a lot of money.”

According to Ramokgopa, it will cost Eskom around R210 billion to increase the network capacity. However, Eskom’s balance sheet cannot finance this investment.

Yelland says the big question is who will pay for it.

“There is money, but Eskom does not have enough. The money that Eskom receives from the national treasury is also part of a bailout and must be used to repay loans. It cannot be used to finance new capital expenditure,” he says.

“Eskom must look at an innovative business model to make it possible to finance the expansion of the power network. One of these possibilities is to involve the private sector to build the necessary assets and then transfer the ownership and operation of them to Eskom so that Eskom can pay them off over a specified period of time rather than financing them out of their own pockets in advance.”

Ramokgopa says this is one of the options that Eskom is considering, but costs must be looked at so that consumers do not pay even more over time.

Rudi Dicks, head of project management in the presidency, who was also at Sunday’s media conference, says a “large part” of the R210 billion will be financed by the partnership for a fair energy transition (JetP). The JetP is the climate funding agreement concluded in 2021 with several developed countries.

“There are various discussions between the Treasury and international partners about what form this will take as we look at different models of investment to solve the shortage of network capacity,” he says.